Contributed by Ryan Huang, University of Michigan.

This work is supported by the eBPF Foundation Academic Research Grants.

eBPF has grown into one of the most exciting technologies in modern systems, providing a safe and expressive way to dynamically extend the Linux kernel. It now powers observability, networking, tracing, profiling, security, and more. As the eBPF ecosystem expands its use cases, developers increasingly run into a tension: the verifier, the component that checks a given eBPF program abides by safety rules before running the program, can sometimes be too restrictive; paradoxically, the verifier can also miss certain unsafe patterns.

Our team has been developing ePass, a new framework that helps address this tension by introducing verifier-cooperative runtime enforcement. ePass improves programmability without compromising safety, and enhances safety beyond what static verification alone can provide. This blog post provides an overview of ePass, its current status, and future roadmap.

When Static Verification Isn’t Enough

The verifier is a central component of the eBPF ecosystem. It uses static analysis to inspect eBPF bytecode at load time and decides whether it is safe to run. To stay sound, it must over-approximate possible program behaviors. In practice, that means when it cannot conclusively prove something is safe on all paths, it rejects the program even when the actual runtime behavior would be fine.

As a result, developers can run into the problem of false rejections. Typical examples include programs whose loops have data-dependent bounds that the verifier cannot track precisely, or programs that index into arrays or maps using values derived through helper calls or bit-masking. In these situations, users often know their program logic is safe, but they must contort the code to convince the verifier: splitting logic across multiple tail calls, adding manual masks, or cloning nearly identical code paths. These workarounds add complexity, hurt readability, and sometimes introduce new bugs of their own.

At the same time, static checking alone cannot capture every nuance of runtime behavior. The verifier operates on bytecode and abstract register states; it cannot see, for example, which exact stack bytes were initialized, or every subtle way misclassified helper arguments might interact with kernel code. Real CVEs have arisen from these gaps, including uninitialized stack reads, pointer leaks, and cases where invalid arguments to helpers slipped past the verifier but caused exploitable behavior during execution.

Efforts have been made to improve the verifier’s analysis, which helped alleviate some of these issues. However, the core problem remains. The verifier itself has also become difficult to evolve. Adding new helpers, map types, or program types often implies more special cases and more intricate state tracking. There is a growing sense that static verification alone cannot scale to meet both programmability and safety demands while keeping the complexity manageable.

The ePass Vision: Verifier-Cooperative Runtime Enforcement

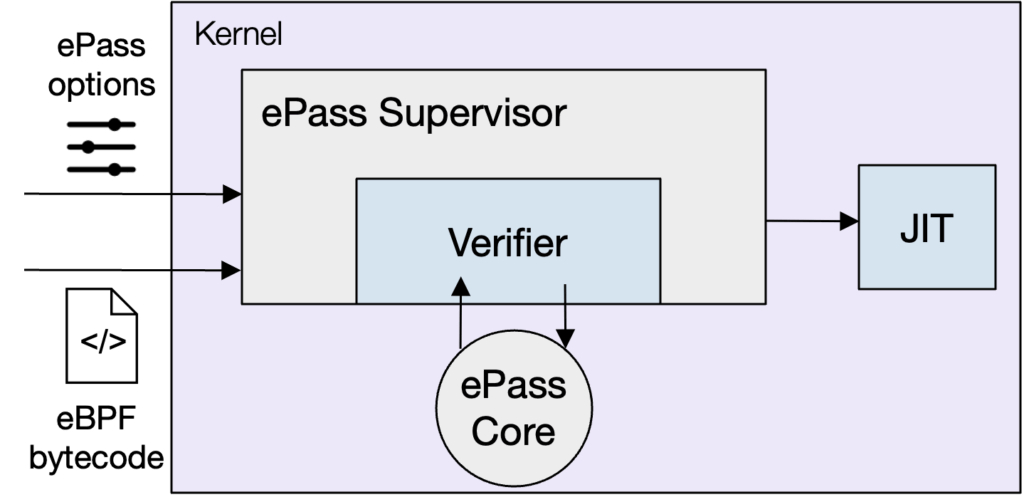

Figure 1. Overview of ePass

ePass is built around a simple insight: some safety properties are fundamentally hard to prove statically but are reasonable to enforce at runtime. Instead of making the verifier ever more complicated, we can keep it as the core root of trust and augment it with structured runtime enforcement.

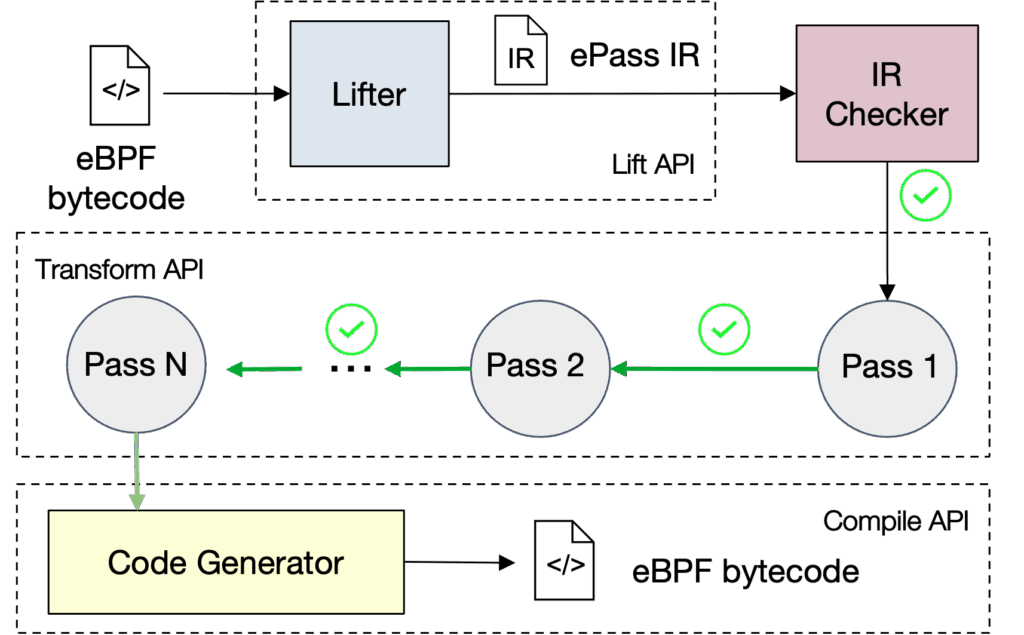

To do this, ePass extends the eBPF loading pipeline. It first introduces an SSA-based Intermediate Representation (IR). This IR is designed specifically for eBPF: it has virtual registers, explicit control-flow graphs, and annotations that preserve the connection back to the original bytecode and the verifier’s analysis. When a program is loaded, ePass lifts the bytecode into the IR. Once in IR form, ePass runs a series of transformation passes that can insert runtime checks, repair verifier-triggered issues, or optimize code. After these passes run, ePass compiles the IR back to eBPF bytecode and sends it through the verifier again before JIT compilation.

| Categories | API | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Instruction Manipulation | ir_insn *epass_create_ja_insn(epass_env *env, ir_insn *pos_insn, ir_bb *to_bb, enum insert_position pos) | Create a direct jump (JA) instruction jumping to to_bb before or after (defined by pos) pos_insn. |

| void epass_ir_remove_insn(epass_env *env, ir_insn *insn) | Remove an instruction from IR. | |

| BB Manipulation | ir_bb *epass_ir_split_bb(epass_env *env, ir_function *fun, ir_insn *insn, enum insert_position insert_pos) | Split the basic block into two basic blocks at a given position. |

| Verifier Integration | ir_insn *epass_ir_find_ir_insn_by_rawpos(ir_function *fun, u32 rawpos) | Get the IR instruction that the bytecode at rawpos corresponds to. |

| vi_entry *get_vi_entry(epass_env *env, u32 idx) | Get the VI map (Section Supervisor) entry from the instruction index idx. | |

| Miscellaneous | array epass_ir_get_operands(epass_env *env, ir_insn *insn) | Get all the operands of an instruction. |

| void epass_ir_replace_all_uses(epass_env *env, ir_insn *insn, ir_value rep) | Replace all the uses of a VR with another value. |

Table 1. Example of ePass IR APIs

A key design decision is that ePass always operates inside the verifier pipeline. It does not bypass verification or silently sneak in unverified code. Every transformed program is re-verified. The verifier remains the central trusted component, while the checks inserted by ePass are treated like any other eBPF instructions and must comply with all existing safety rules.

To make this practical, ePass includes two main components. The “core” is a compact compiler framework that implements the IR, the lifter, the code generator, and a library of reusable transformation primitives. The “supervisor” sits in the kernel alongside the verifier and coordinates when and how ePass runs. It also enforces policies, such as system-wide limits on instruction counts or which passes may be enabled by regular users versus administrators.

Figure 2. Architecture of ePass core. The green arrow means that the IR is passed through the IR checker.

Current Status

Although the project is still evolving, our current prototype demonstrates that this verifier cooperative approach is feasible and useful. We have implemented a dozen passes, covering three main themes: repairing verifier false rejections, strengthening runtime safety, and optimizing code.

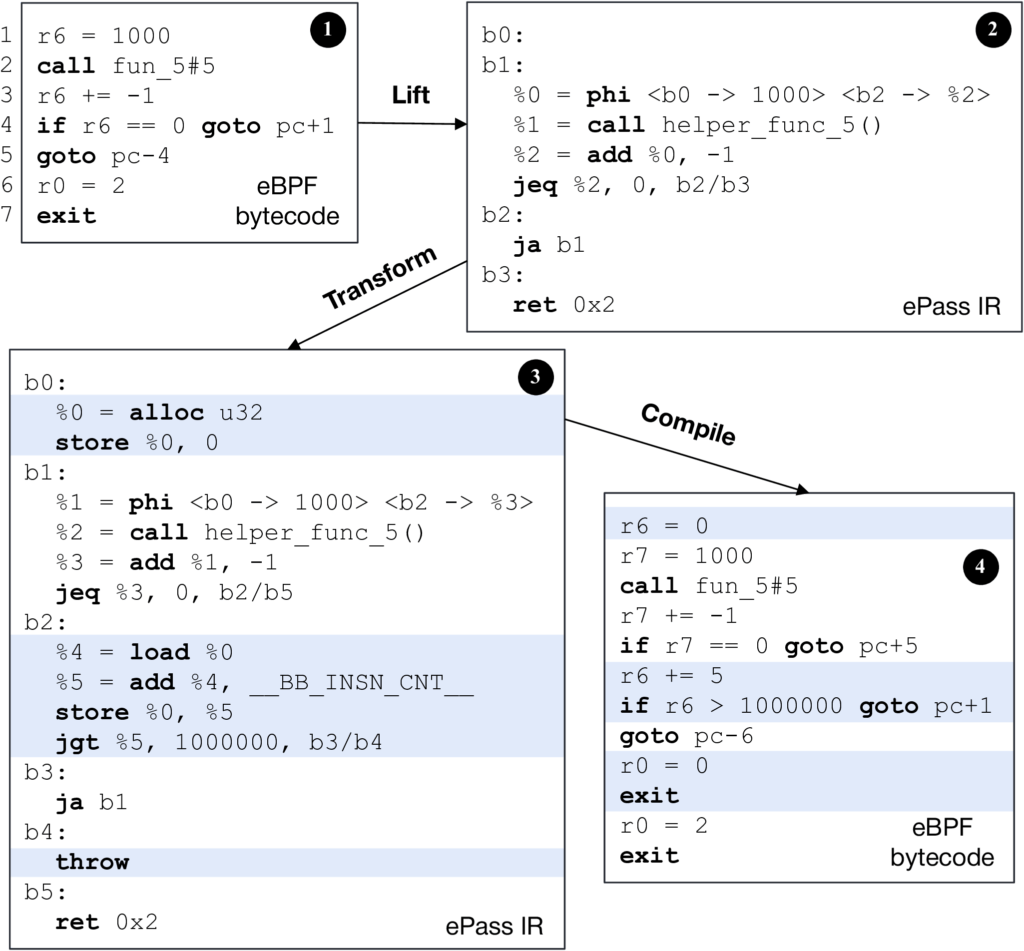

One example is the instruction counter pass. Many developers have encountered confusing “program too large” or instruction-limit errors even when they know their loops will terminate quickly at runtime. ePass tackles this by moving part of that responsibility to runtime. The counter pass instruments programs with an instruction counter that is incremented at carefully chosen locations. If the total executed instructions exceed a configured limit, the program is safely terminated. This approach allows us to keep a global budget on execution without forcing the verifier to conservatively assume worst-case iteration counts for every path. In tests, this pass enabled real world programs rejected by the verifier to execute safely without exceeding actual limits and with negligible runtime overhead.

Figure 3. A sample workflow of running the counter pass. The code is simplified for readability. ❶ is the input eBPF bytecode, ❷ is the lifted E PASS IR, ❸ is the transformed IR after running the pass, and ❹ is the compiled eBPF bytecode. Highlighted lines are the instructions added by the pass.

Another example is the MSan pass for uninitialized stack handling. The verifier historically tracks only how deep the stack is used, not whether every byte has been written before being read. ePass introduces a shadow memory region to track initialization status. When the program writes to the stack, the corresponding shadow bytes are marked initialized; when it reads, ePass checks the shadow state and terminates the program if it accesses uninitialized memory. This directly addresses a class of bugs and vulnerabilities where programs, previously accepted by the verifier, used uninitialized stack contents at runtime.

ePass also tackles helper-related exploits through a helper validation pass. The verifier’s range analysis is used to infer what arguments to helpers should look like. ePass then inserts runtime guards before those helper calls to ensure the values stay within the inferred safe ranges. If a malicious or buggy program later manages to steer arguments outside those bounds, the runtime check will detect and stop it before the helper executes in an unsafe way.

Beyond these, ePass includes passes that insert index-masking logic for dynamic array or map access, passes that simplify and canonicalize stack usage, and classic compiler transformations like dead-code elimination and compactness optimizations that merge redundant operations.

To understand how well ePass works in practice, we evaluated it on several aspects: programmability, safety, correctness, and performance. For programmability, we collect 23 real world eBPF programs that had been rejected by the verifier despite being semantically safe. These came from GitHub, Stack Overflow, and open source projects such as Cilium and Falco. With ePass enabled and appropriate passes configured, 21 of the 23 programs are successfully transformed, re verified, and allowed to run. The remaining two cases involve limitations of the current prototype across tail calls. In both cases, we verify that ePass does not compromise correctness by accepting unsafe variants.

For safety, we evaluate both fuzzing and real vulnerabilities. Using an eBPF fuzzing toolchain, we generated thousands of programs that attempted out-of-bounds accesses, uninitialized reads, or invalid pointer manipulations. Programs that were correctly rejected by the verifier stayed rejected under ePass, while programs that passed verification but would misbehave at runtime were caught by the inserted checks. We then analyzed recent eBPF-related CVEs and found that 14 of them fall into categories that our existing passes can mitigate.

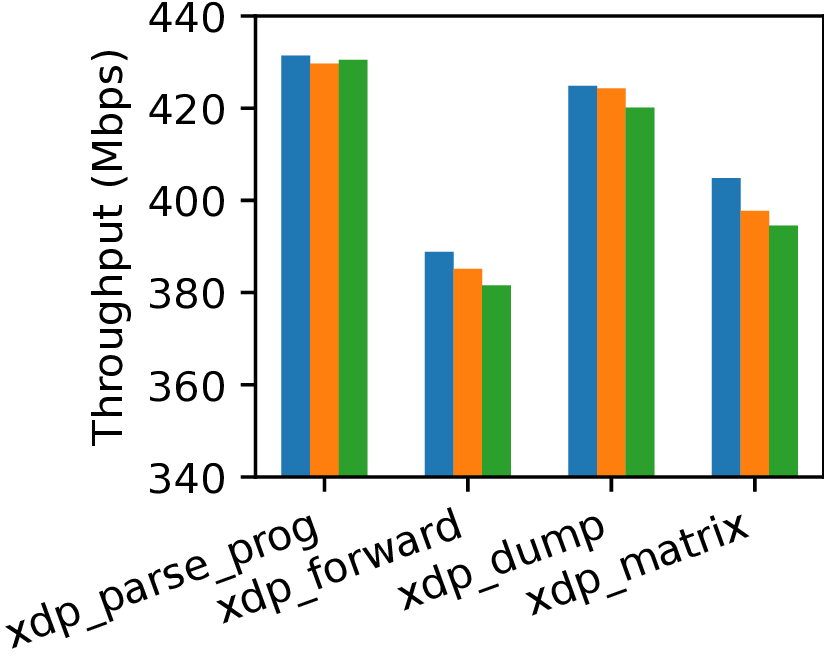

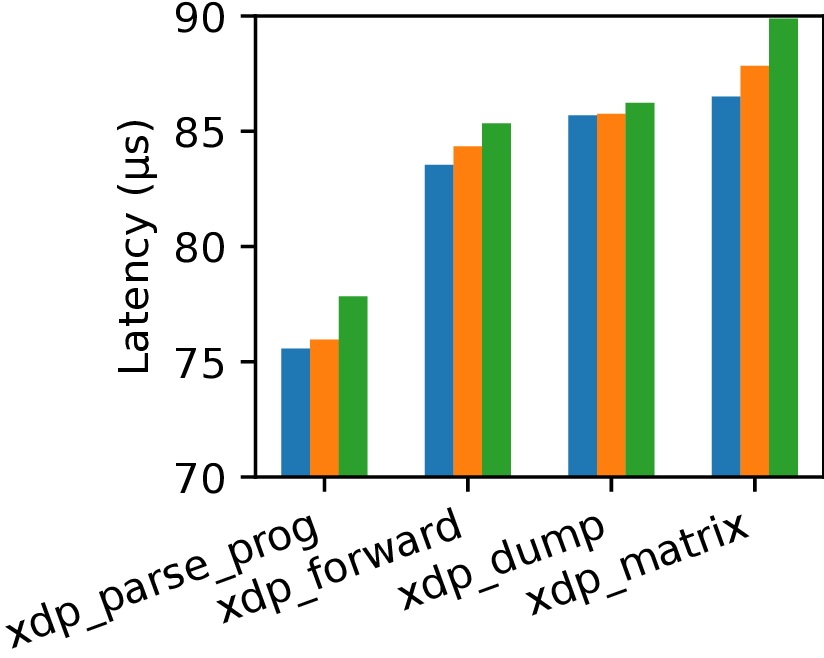

Performance is often a concern when adding any runtime checks, particularly for performance critical environments like XDP. We therefore measured both throughput and latency for representative XDP programs, with and without ePass passes enabled.

|

|

Figure 4. Throughput and latency of four XDP programs. Blue (left) is without ePass, orange bar (middle) is with counter green bar (right) is with MSan pass.

Even with heavier instrumentation like MSan, the impact is under 2% on average for throughput and latency. Lighter passes such as the instruction counter have even smaller overhead. For regular system workloads, we run Falco in the background with ePass and benchmark the system using lmbench and Postmark. The overheads are negligible.

From a correctness perspective, we validated ePass on 504 human-written programs drawn from real projects, as well as 10,000 fuzzer generated programs. For all the tests where programs were valid, the transformed versions behave identically to the originals: same verifier decisions, same outputs, and no crash or divergence introduced by ePass itself.

Roadmap

The current results show that our approach is promising. There is much more we plan to do. The next phase of the project focuses on turning ePass into a robust and highly usable framework. In the near term, we are working to extend and refine the ePass IR, stabilize the kernel integration, and increase compatibility with recent kernels. One high-priority task is to strengthen the testing framework so that bugs in the passes or ePass components can be caught early. We will also make the APIs easier to use. We aim to only require tens of lines of code for developing a typical new pass. In parallel, we will look for more compelling use cases and grow the library of transformation passes to cover diverse scenarios.

We are also thinking about introducing a policy framework for administrators. Rather than enabling passes one by one, operators will be able to select profiles that each map to a curated set of passes. This will make it easier for distributions, cloud providers, and platform teams to adopt ePass in ways that match their performance and feature requirements.

Finally, we will improve the ePass documentation, add examples and tutorials, share technical papers, present in conferences, and engage with the community for feedback. Our long-term goal is for ePass to integrate smoothly with the evolving eBPF ecosystem.

Get Involved

ePass is open source and available at:

https://github.com/OrderLab/ePass

We invite eBPF users, kernel developers, and platform builders to try it out, report issues, and share real programs that are incorrectly rejected by the verifier, use workarounds due to programmability restrictions, or expose tricky unsafe behavior. Those real-world examples are the best way for us to shape ePass into something that is truly useful to the community.

With the support from the eBPF Foundation, we are excited to keep pushing in this direction. We hope that verifier-cooperative runtime enforcement becomes a core part of the eBPF ecosystem: unlocking more expressive programs, tightening safety guarantees, and keeping kernel extensibility both powerful and trustworthy.